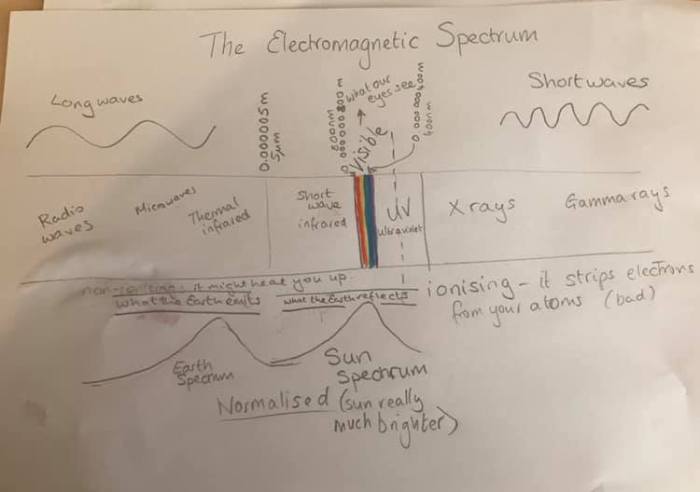

One of the most important bits of physics to understand, before we get to climate, is what blackbody radiation is all about. So this builds on lesson 1 about the electromagnetic spectrum. Here I’ve zoomed in on the middle bit and turned the scale around (so now IR – long wavelengths – are on the right and UV – short wavelengths – are on the left).

When something is perfectly black, it will absorb all energy falling on it (nothing is reflected) but if that were the whole story, things would get hotter and hotter for ever. Of course, that does not happen – because black bodies also radiate energy away as “light”. The blackbody curve (see picture) shows how black objects radiate “light” – and what wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation are radiated. That depends on how hot the object is. Max Planck wrote down the theory of the blackbody curve back in 1900 and, almost by accident, invented quantum mechanics in the process (but let’s not get side tracked down that interesting alleyway).

As a blackbody gets hotter it emits more light and the spectrum shifts “up and left” (so more light, and the peak moves to shorter wavelengths).

Now that’s all a bit physicy and esoteric so let me link it to things you already know. You already know the idea of “red hot” – as you start heating an electric stove and it gets hotter there comes a point where it starts to glow red. What has happened is that the curve has shifted up and left enough that there’s enough red for you to see it. That’s somewhere around 600 degC (scientists call this ~900 kelvin as we like to start temperatures at absolute zero).

If you keep heating something up it will go orange hot as you start getting orange and red wavelengths too. Your old fashioned tungsten lightbulb (I hope by now replaced by an LED!) had a tungsten filament at around 2500 K – 3000 K (subtract 273.15 to convert to degrees Celsius). That was a yellowy-white. The outside of the sun is about 5500 K and that is “white hot” – the peak of the blackbody curve is in the middle of the visible so all the wavelengths are there and they mix to look “white” (remember Newton splitting white light with a prism to show all the wavelengths are there). There are stars hotter than our sun that are “blue hot” as their peak is in the UV and their spectrum is already dropping in the visible – with blue much higher than red.

But you can see from the graph that the sun also emits plenty of what we call “short wave infrared” (incidentally that was the problem with tungsten lamps – almost all their radiation was actually infrared and thus invisible.).

Of course it doesn’t stop there. Almost everything has a blackbody curve. Blackbodies around room temperature (~300 K) have a peak at wavelengths around 10 micrometres. That’s a wavelength we call “the thermal infrared” and it’s what those thermal imaging cameras you see in science museums (the ones that give people red faces and blue noses and black glasses) measure. Even space itself has a microwave blackbody signal – that represents a temperature of around 3 K (just above absolute zero) – and is the temperature the Big Bang has cooled down to.

Now real objects aren’t perfect blackbodies – they reflect some light – but these basic ideas hold up. And the sun and earth are, to a first approximation, blackbodies at 6000 K and 300 K respectively. And this matters because it’s how the sun heats the Earth up and how the Earth cools back down again.

(Don’t worry, we’ll start getting onto the climate soon! This is the background stuff that makes the explanation meaningful. I know this stuff is hard, so please feel free to ask questions. Lesson three will involve my favourite equation and how atoms and molecules emit and absorb single wavelengths of light rather than blackbodies emitting and absorbing broad spectra … and then we’ll start talking about the temperature of the Earth!).